|

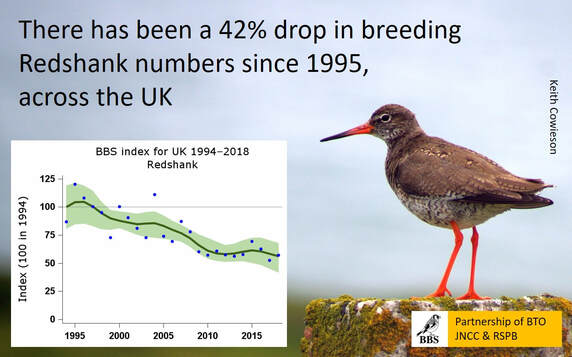

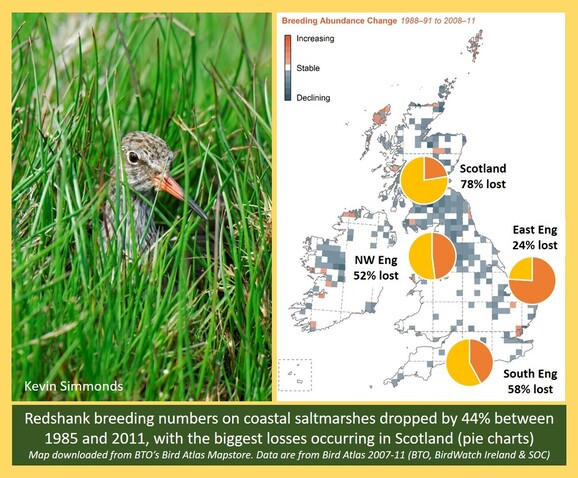

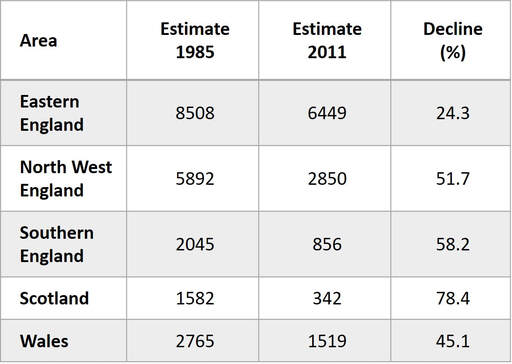

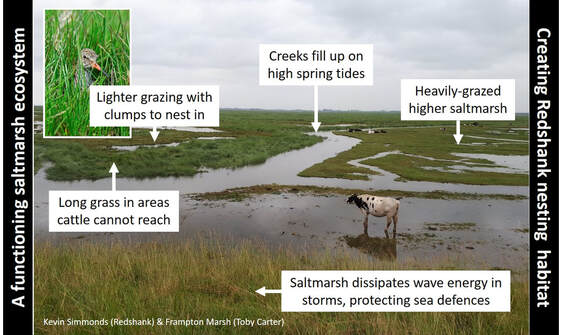

Guest blog by Graham Appleton, author of WaderTales. He has studied waders for over 40 years and is currently involved in wader research in the UK and in Iceland. He was Director of Communications at The British Trust for Ornithology until 2013 and is now a freelance writer and broadcaster. The noisy calls of Redshank, as they warn others of the approach of predators, proclaim ownership of territories or defend their chicks, is one of the most distinctive sounds of the coast during the summer. The RSPB and National Trust’s Life on the Edge aims to increase numbers of breeding Redshank by protecting and improving the saltmarsh habitat in which they breed. Redshank is an amber-listed species of conservation concern in the United Kingdom, with the most recent estimates of breeding population changes showing a drop of 42% between 1995 and 2018 (Breeding Bird Survey) and a larger decline over the period since 1975. About 25,000 pairs of Redshank breed in the UK (link to APEP4), with half of these nesting in coastal saltmarshes. Redshanks hide their nests in tussocks of vegetation but the chicks feed in more open environments, particularly around the edges of muddy pools. Nesting on saltmarshes Saltmarshes are intricate, dynamic habitats, where land meets sea. They are highly productive ecosystems, rich in plants, birds and insects. Traditionally, they would have been grazed by herbivorous mammals and waterfowl but, in the absence of free-roaming animals, the only way to maintain the short but diverse swards that harbour specialist plants and animals is to employ the services of cattle and sheep. Although saltmarsh still covers large areas, it is estimated that over 50% has been lost or degraded globally, with further losses occurring as saltmarshes are being squeezed between rising sea levels and hard sea defences that protect coastal settlements and farmland.  Anyone who has been out on a saltmarsh will know that they are not easy places to navigate, as they often have complex systems of meandering creeks that vary from small ankle-breakers hidden in the vegetation to deep, fast-flowing channels with slippery, muddy sides. With some local knowledge, it is possible to make your way from the sea-wall to the edge of the saltmarsh along a route that lies between two creek systems. On the other hand, travelling along the muddy, salting edge, parallel to the sea-wall, is difficult as it involves crossing creeks. Grazing animals face the same navigation problems; it’s a lot easier to graze wide expanses of the upper marsh than the outer areas that are dissected by deep creeks. These upper areas, with a mixture of short grass and clumps of longer vegetation, in which to hide nests, are also the ones that are favoured by breeding Redshank. How many Redshank breed on saltmarshes? A 2013 paper by Lucy Malpas (now Lucy Mason) in Bird Study brought together evidence of declines in saltmarsh-breeding Redshank over a 26-year period. An estimated total of 21,431 pairs were found to be breeding on British saltmarsh in 1985 but this had dropped to 11,946 pairs in 2011, with the highest proportion of the remaining population found in East Anglia. The 2011 survey showed that there were regional variations (see table), with the biggest declines in Scotland but also losses of over 50% in south and Northwest England. Looking at the way that saltmarshes were managed, Lucy found that Redshank declines were less severe on conservation-managed sites in East Anglia and the South of England, where grazing pressures remained low, but more severe on conservation-managed sites in the Northwest, where heavy grazing persisted. At the end of this Bird Study paper, Lucy and her colleagues suggest that saltmarsh-breeding Redshank declines are likely to be influenced by a lack of suitable nesting habitat. Conservation management schemes and site protection, implemented since 1996, appeared not to be delivering the grazing regimes and associated habitat conditions required by this species, particularly in Northwest England. Although habitat changes may not be linked to unsuitable grazing management in all regions, they suggested the need for a better understanding of grazing practices and consideration of potential long-term management solutions. Grazing levels and Redshank numbers Intensive grazing leads to a very short uniform sward, lighter grazing produces a more uneven patchy sward with diverse heights, whilst no grazing can leave saltmarshes with dense communities of coarse grasses. For Redshank, that need clumps of tall vegetion in which to hide their nests and more open areas in which chicks can feed, light grazing is a key management tool. Elwyn Sharps and colleagues, working on the salt marshes of the Ribble Estuary in Northwest England, investigated how grazing regimes worked for the local Redshanks. Elwyn showed that the risk of Redshank nest predation increased from 28% with no breeding-season grazing to 95% with grazing of 0.5 cattle per hectare per year, which is still within the definition of light grazing. You can read more about this in the WaderTales blog Big Foot and the Redshank Nest. In follow-up work, Elwyn showed that livestock play an important role in creating the clumps of Festuca rubra nesting habitat preferred by Redshank nesting on the Ribble Estuary but that even low-intensity conservation grazing can create a shorter than ideal sward height, potentially leaving Redshank nests more vulnerable to predators. One of the missing elements from Elwyn’s first two papers about grazing levels was an understanding of the behaviour of cattle on saltmarsh. In the next piece of work, Elwyn and colleagues tracked the movements of individual cattle, using GPS collars, and assessed the vulnerability of nesting Redshank, using dummy nests. In a 2017 paper in Ecology & Evolution, they showed that cattle spend their time in the same areas of saltmarsh as the ones that the Redshanks like to nest. Their conclusion is that “grazing management should aim to keep livestock away from Redshank nesting habitat between mid-April and mid-July, when nests are active, through delaying the onset of grazing or introducing a rotational grazing system”. Do conservation payments deliver? In recognition of the importance of saltmarsh habitat, agricultural grants have been available to support the management of saltmarshes, with a focus on providing an appropriate level of grazing for a range of plants, birds and insects. In their 2019 paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology, Lucy Mason and her RSPB colleagues asked some whether these agricultural subsidies are being well spent. This work is described in the WaderTales blog Redshank - the warden of the marshes. They concluded that, although there is sound scientific evidence as to how saltmarshes should be managed, it is difficult to encourage land managers to implement recommendations when these go against traditional farming practices and economic gain. Raising cattle on saltmarsh is hard work, in terms of stock control, but requires no fertiliser inputs. These ‘mobile mowing units’ stop saltings from becoming long and rank, thereby creating spaces in which a rich plant and grass community can flourish, where geese and waterfowl can graze during the winter months, and potentially providing nesting spaces for breeding waders, such as Redshank. Lucy and her colleagues conclude that agri-environment schemes are the only mechanisms through which saltmarsh conservation grazing can be implemented on a national scale, so it’s important to make sure that they are as effective as possible. By working together, it is hoped that policymakers, researchers and managers can refine conservation guidelines which are used to create management schemes that attract subsidies. Although half of the UK’s Redshank nest on tidal saltmarshes, significant numbers also nest in lowland wet grassland, on nature reserves and on low-lying pastoral farmland. These freshwater systems can be managed for breeding waders such as Lapwing, Redshank and Snipe. You can learn more about the tools available in the WaderTales blog Tool-kit for wader conservation, which summarises work led by Jen Smart (RSPB) and Jennifer Gill (University of East Anglia). One more problem!

As coastal communities are aware, sea-levels are rising and so is the incidence of summer storms. This is not good news for species that nest on saltmarsh, such as Redshank. In a naturally functioning ecosystem, the coastline would be receding, and Redshank would be moving inland. With hard sea walls protecting towns and farmland, it is hoped that new saltmarshes can be created in a few low-lying areas and that conservation management can be focused upon these wader hotspots. These new saltmarshes will not only provide space in which to develop biodiverse habitats that are great for waders, they can also capture carbon and reduce damage to coastal defences.

1 Comment

Mrs Sharon Buchan

14/5/2022 14:31:49

We are trying to save at least 8 redshank nests and more than a dozen lapwing nests from being ploughed in on Monday. We are in north east Scotland and the nests are on the Ythan estuary.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

Photo credits: Oystercatcher by Katie Nethercoat (rspb-images.com)

LOTE Logo credits: Saskia Wischnewski |