|

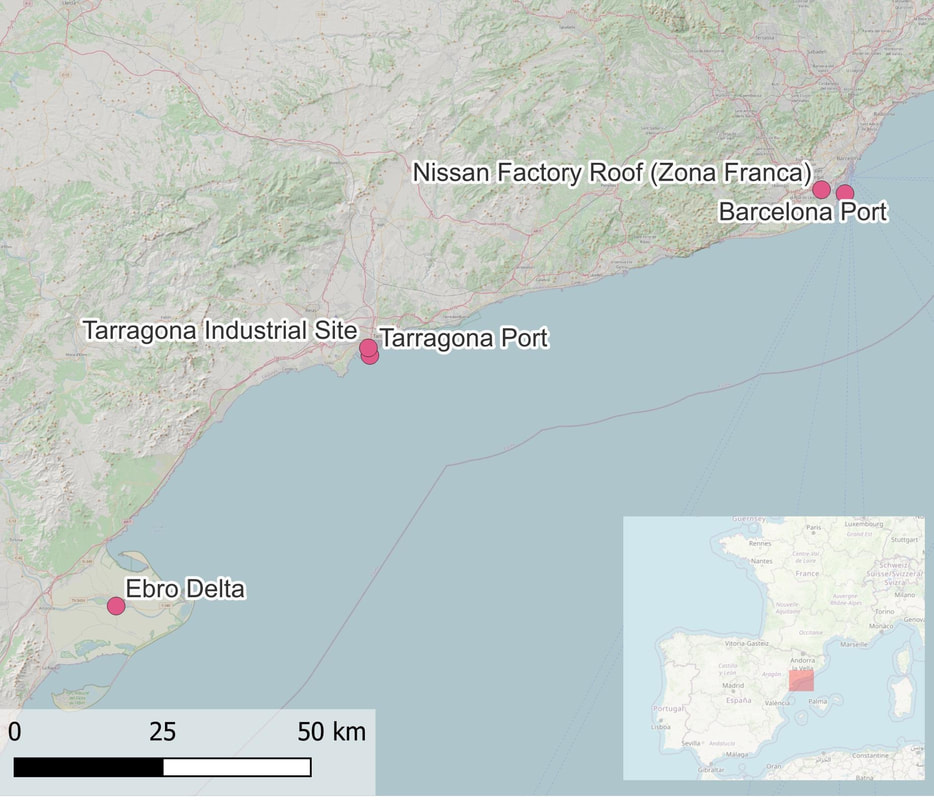

Blog by Sarah Dalrymple, RSPB Senior Species Recovery Officer Last week I was out in and around Barcelona with Ricard Gutierrez and his colleagues from the Fauna Conservation Unit of the Government of Catalonia, to see how they monitor and protect breeding colonies of Audouin's Gull (Ichthyaetus audouinii). The current European population estimate for this species is estimated at 15,900 to 21,800 pairs, from just 1,000 in 1970s. Their biggest colony at the Ebro Delta, in Catalonia, was hit hard by predators in the early 2010s. The birds moved to more urban settings: at the docks in Barcelona and Tarragona, about 80km to the west, and at a rooftop colony on a factory in Barcelona’s industrial zone. Barcelona Port At Barcelona port, a few hundred gulls chose to nest on land put aside for development. To discourage them away from this area, and onto a nearby protected area put aside for them, the port landowners employed someone to walk up and down the development area all spring and summer, preventing the birds from settling in this area. The area on top of a nearby Harbour Wall was designated as compensatory nesting habitat. With the birds unable to settle on the development land, they were encouraged to move to this location by placing simple bits of shelter. This was amazingly successful; rocks, pipes, branches, everyone had a nest or two (or four!) next to it. 2023 found 838 nests here, an increase from 439 in 2022. Zona Franca, Barcelona The rooftop at Zona Franca covers nearly 7ha, where we counted 438 nests of Audouin’s, alongside a large colony of Yellow Legged Gulls (Larus michahellis). The Yellow-leggies outcompete the Audouin’s for space, pushing them further away into the corners of the site. Like at the docks, nests were frequently found next to something, in this case pipes, rooftop structures, and in one case – a cactus. This is the only known roof-top nest site for Audouin’s gull. 438 nests were counted here in 2023, a slight decrease from 453 in 2022, but still up on the 205 pairs counted in 2021, when the colony was first discovered. Tarragona At Tarragona, harbour authorities have fenced off the two nesting areas of these birds. Like at Barcelona, access to the dock area is restricted, so they are protected against casual disturbance. Again, the gulls preferentially nested next to even the smallest bit of shelter. At Tarragona port, the two sites held 651 nests in 2023, an increase from 439 in 2022 but still down on the peak of 1,043 nests in 2018. The work of the Fauna Conservation Unit has involved not just monitoring and protecting, but working with the commercial landowners at the docks and the factory to secure and protect the nest sites of this species. It has absolutely paid off; increasing the number of colonies provides security for the species, and by their locations, these colonies are protected from most predation and disturbance. It is great to have strong evidence of the positives of colonies sited in urban and industrial areas. At the Ebro Delta, I was shown the simple measures that have been put in place to help protect beach nesting birds such as Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrines) from recreational disturbance. As well as signage, extensive areas have been fenced off with rope fencing to prevent vehicle access. We spoke about how with very similar issues in the two countries when it comes to beach nesting birds, there is a lot of potential for co-operation and information sharing. This was a fantastic visit. It was great to meet Ricard and his team, and I cannot thank him enough for taking the time to welcome me and show me the gull colonies in these incredible places, as well as the pelagic boat trip, excellent birding around the Ebro Delta and some amazing Catalan tapas. If interested, more information can be found here: Government department website: mediambient.gencat.cat/ 2022 season summary: birdspain.blogspot.com/2022/06/la-gaviota-de-audouin-en-catalunya-en.html

0 Comments

Blog by Leigh Lock, RSPB Project Development Manager The global and national threats to seabirds are widely recognised and much focus understandably links the status of seabirds with the state of our seas which is where most seabirds spend most of their time. But what about the state of the ‘land’ where seabirds spend the breeding season – a critical phase of their lifecycle? As a land-based observer of birds on the coast for decades, the growing pressure on breeding seabird sites has been a major concern and I feel we have reached a tipping point where if we don’t act now there will be no safe nesting space left for seabirds in some areas in the future. Therefore, I was excited by the prospect of Seabird Conservation Strategies being developed within all four UK counties by government – each will set out the strategic needs of our seabird species and set out a route map for their recovery. This process in England has been led by DEFRA and NE. But I wanted to make sure that the current state of seabird colonies in England was reflected in this process and that the thoughts and concerns of those most close to the sites – the site managers, conservation officers etc responsible for these areas– were captured. So I contacted as many of those key people around the coast as possible to gather views on pressures impacting on seabird colonies. This is probably the first time such an assessment has been made. Much of this information gathered was necessarily subjective, being based on the opinions of the site managers, and others. However, expert judgement provided by the site managers most familiar with the sites, and their issues, constitutes the best available evidence on issues affecting England’s breeding seabirds. The process does present a ‘ground truthing’ to compare with other available data sources so that all the available information together can be used as ‘weight of evidence’ to identify the main issues and develop solutions to them. Working closely with colleagues within NE, we then looked to align this rather broad-brush assessment of pressures on colonies with other data sources being carried out to inform other areas of the strategy. Information was gathered on 222 natural sites (i.e., excluding urban gulls) and covering 24 seabird species – this representing the vast majority of England’s seabirds. Pressures were assigned to predefined categories including disturbance, habitat loss, predation, invasive species, disease, and control. Note that the assessments were carried out before the widespread and serious impacts of Avian Influenza (AI) were recorded in England in 2022. Overall, the most widespread was disturbance (see below), with both habitat loss and predation impacting on over 50% of the sites. The other pressures were recorded at far less sites, although their impacts at individual sites could be very significant (e.g., invasive species on islands). There are plenty of discussion points emerging from this but below I have pulled out just three. 1. The widespread impacts of disturbance Disturbance is the most widely reported pressure affecting England’s breeding seabirds impacting on 89% of the coastal sites, all sites supporting species like little tern and Sandwich tern, and 100% of English SPAs with breeding seabird features. Site managers see disturbance as THE rapidly growing issue, and human recreational disturbance at coastal sites is predicted to increase. Disturbance of nesting seabirds is caused by a range of recreational activities – beachgoers, dogwalkers and recreational fishers on land, and recreational watercraft such as jet skis, paddleboarders from the sea. Although disturbance is particularly an issue for ground-nesting birds such as terns and gulls at soft coast sites, I was also surprised how widely it was reported at cliff colonies and even offshore islands where birds vulnerable to disturbance from the sea. Disturbance at nest sites can have significant negative impacts on seabird breeding success through increased exposure of eggs and young to predation and the elements and can lead to the abandonment of nest sites and even entire colonies. What I see are overstretched, under resourced conservation organisations trying to manage coastal sites where nature conservation should be the priority, but recreational interests prevail. Many areas have wardens to ‘protect’ nesting birds and engage with the public. But without zonation policies and legislation to restrict certain activities, on-site teams of staff and volunteers face an uphill battle, and the birds using these sites face a bleak future. 2. Sea level rise and coastal erosion present an existential threat to some of England’s most important seabird colonies. Within England, most seabird sites occur on ‘soft coast’ sites – nearshore islands, salt marshes, lagoon islands and shingle banks. These habitats are under massive pressure and the reduction in size and quality of nesting habitat is the second most widespread pressure in England. Without intervention, 2,000 Ha of protected coastal habitats is predicted to be lost in England by 2060 with even greater areas being functionally lost as breeding habitat due to regular flooding. Previously, these losses were mainly from development and land claim, but the key future threats to coastal habitats are from climate change-related sea level rise, coastal erosion, and coastal squeeze. Mean sea levels in the UK have already risen by approximately 17 cm since the start of the 20th century and climate predictions show that they will continue to rise under all emissions scenarios until at least the year 2100. Increases in sea level rise are difficult to predict but are likely to be greatest in southern and eastern England where some of the largest colonies are. Rising sea levels mean that more coastal seabird breeding habitat will be lost, and the risk of intermittent flooding of nest sites is also increased. In addition to mean sea level rise, the risks of extreme sea levels and flooding are compounded by increases in storm events. Species that nest on the ground in sand and shingle habitats, such as terns and gulls, are particularly at risk, as large areas of these types of habitats can be lost rapidly with only minor increases in sea level. Many current breeding sites for terns and gulls on beaches and low-lying near-shore islands which are likely to become unsuitable or be lost entirely within the next 10 years. Little terns are particularly at risk because they tend to nest just above the high-water mark and in recent years high proportions of the UK’s little tern nests have been flooded out during spring tides and storm surges. Short term fixes are in place at many sites. Habitat management to keep sites open, recharge of shingle islands to raise their levels above highest tides but longer-term measures are required to ensure that seabirds have safe nesting sites for future decades not just the next few years. This involves factoring seabird breeding habitat into multi-stakeholder strategic management planning eg Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs), Nature Recovery Networks (NRNs), Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS)) and the implementation of the government’s 25-year Environment Plan. Breeding seabirds should be considered in full as part of these overarching plans and programmes, to ensure that existing breeding sites are adequately managed, and new breeding habitat is created and maintained, and linked to funding streams like Biodiversity Net Gain.  Beneficial use of dredged sediment can be used more widely to provide habitat for nesting seabirds and provide natural sea defences – here 50,000 cubic metres of sediment delivered through @ProjectLOTE working with Harwich Haven Authority, EA and the landowner supports the most important little tern colony in Essex (c) JPullen 3. Avian Influenza and the in-combination effects.

As mentioned above, the assessment was carried out last year before the impacts of AI were recorded in England this summer. Disease was not noted as a significant pressure and has not really impacted on seabirds since botulism on gulls in the past. But the impacts of AI in 2022 have been severe – impacting significantly on the largest UK and England colonies of both roseate and sandwich terns – Coquet and Scolt Head Islands respectively -with 1000s of dead breeding adults and large-scale breeding failure at these colonies. we await a full assessment of the impact of AI on seabirds in 2022 and how it might impact in the future. But think of the conditions under which AI was able to make such an impact. The ‘in combination’ effects of habitat loss, predation, disturbance have pushed seabirds to the edge – habitat loss squeezing seabirds into fewer and fewer suitable areas, which then become honey pots for predators, and even these few special sites coming under the unbearable pressure of disturbance. All our eggs in fewer and fewer baskets. And then a disease comes along which thrives in conditions where it can spread rapidly amongst individuals in closely packed colonies. To have seabird populations that can be resilient to AI and other diseases, we need more space for them to nest safely, allowing more colonies to thrive, and allowing more mobility from site to site to respond to changes in local conditions. Building resilience to disease and other pressures, requires spreading the risk – more and bigger sites, better managed. For this we need to rethink how our coast is managed. The report The full report is on the documents page of this website. Lock, L., Donato, B., Jones, R., Macleod-Nolan, C. 2022 England’s breeding seabirds: A review of the status of their breeding sites and suggested measures for their recovery. RSPB and Natural England report. The report highlights the most important sites and actions for the recovery of seabirds in England. The recommendations from this report on site management have been incorporated into a wider set of recommendations covering the full suite of seabird ecology -under four categories -breeding, feeding, surviving and knowledge. These recommendations have been made by NE to DEFRA to inform the further development of the England Seabird Conservation Strategy and the implementation of the 25 Year Plan. The Strategy should be available early in 2023. Through ProjectLOTE we will continue to advocate for these changes and work with stakeholders all-round the coast to deliver what we can to help seabirds. Final thoughts There are probably few more committed and enthusiastic workers than those managing seabird colonies and they are doing a brilliant job holding the line against growing pressures from all directions. But they need help. For all the above reasons, the England Seabird Conservation Strategy couldn’t come at a better time, and we must all hope that it brings a step change in the priority and resources allocated to management of seabird colonies in England. Over to you DEFRA. Thanks to all those who contributed information towards this assessment. Good luck to all of you with your challenges ahead. Guest Blog by Will Bevan, RSPB Beach Nesting Bird Field Officer The UK is a nation of dog lovers, with an estimated 12 million pups in UK homes and a large increase in dog ownership since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. We are also a nation of wildlife lovers, with the RSPB alone having over 1.1 million members, and many choosing to visit nature reserves and local wildlife sites in their free time. The two are by no means mutually exclusive, and dog ownership is a fantastic way to stay active, get outside, and appreciate the natural world. The RSPB encourages responsible dog walking on its nature reserves, and in the wider countryside, but what does this mean for dog owners, and why is it necessary around our wildlife? What is responsible dog walking? Responsible dog walking means:

Why is this necessary? Dog owners are often passionate advocates for the environment and possess a wealth of knowledge about the wildlife on their local patches where they regularly go for walks. Sadly though, there are times when dogs can cause major disturbances by chasing or attacking wildlife. Earlier this year, a ten-month old seal pup well known by locals and nicknamed ‘Freddie’, was basking along the Thames in west London when it was attacked by a dog off its lead. It was rescued by a South Essex wildlife hospital, but tragically its injuries were so severe it had to be humanely put down. The owner was heartbroken and regretted that the dog had not been on a lead but had not thought it was necessary at the time. If you are unsure as to how your dog will react around wildlife, especially if they are young or untrained, it is always better to be sure and put it on a lead. This kind of interaction is an extreme example, but this is not the only way in which dogs can negatively impact on wildlife. A far greater problem is that of disturbance. What is disturbance? For much of our wildlife, humans and dogs are seen as predators, and so they will behave as such when we approach. This is a big problem for ground-nesting birds, who do not feel the safety of being up in a tree or bush. Birds that nest on the ground include our beach-nesting birds, such as little terns and ringed plovers, as well as curlews, lapwings, and oystercatchers. When predators, dogs, or people approach, these birds will leave their nests, trying to distance themselves from their eggs or chicks. They might try to lead the threat in another direction, or mob the intruder along with other nesting birds until it leaves the area. These disturbances mean that eggs and chicks are left unattended, making them vulnerable to predation, to thermal stress from being too cold or too hot, or to being crushed as they are very hard to spot. Constant disturbance can also use up the energy reserves of the adults, who are working hard to incubate their eggs and feed themselves - as well as their chicks after they hatch. Eventually if there is too much disturbance the birds abandon their nests, and although they may try again, if this is too late in the breeding season a second attempt may often be unsuccessful. Disturbance can also be an issue outside of the breeding season, as birds roosting along the shoreline in the winter are often resting and reserving their precious energy reserves. For beach-nesting birds who must share their space with regular beach users as well as the huge influx of people and their dogs on weekends and holidays, this can often be too much. Along with other threats such as predation alongside inundation from high tides and severe storms, increasing disturbance at nesting sites is pushing these species to their limits, with many shorebirds facing declines around the world. Dog owners can make a huge difference to the fate of these birds, as recent research by Professor Miguel Angel Gómez-Serrano from the University of Valencia on Kentish plovers suggests that lone, wandering dogs off their leads disturb birds from their nests almost 100% of the time, more than if they were accompanied by their owner and much more than by someone without a dog. This research also showed that sticking to paths and complying with fencing and buffer zones around colonies reduced the amount of disturbance for beach nesting birds. There is plenty of room for both dog walkers and wildlife, and simple measures such as keeping dogs under control or on leads in certain areas can have a real impact on the fate of many of our bird species. This is only done in certain places or times of the year when it is necessary, and there will usually be signs or wardens on hand to let dog owners know. Space for Shorebirds is a project run by the Northumberland County Council, and one of its main objectives is to reduce the impact of human recreation on bird populations. Part of this involves fostering positive relationships with dog walkers and asks owners to get their dogs to take the Dog Ranger pledge. They share owners’ dogs on social media with the hashtag #dogranger and get them to spread the message about shorebird conservation. Another example is Bird Aware Essex Coast, which aims to raise awareness about coastal birds whilst preventing human disturbance. With fantastic schemes such as this, we can all work together to ensure a bright future for shorebirds where we can peacefully co-exist alongside each other. Look out at the end of July when the RSPB will be hosting ‘Smooch a Pooch’ along the East Norfolk coastline to raise awareness about our beach-nesting birds as well as celebrating our furry friends, with a chance to chat to some of our Field Officers and some tasty treats for the dogs! For more information here is the Facebook link for the event at Winterton Village Hall, Sat 17th July, 8am-12pm. Their contact email is [email protected]. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

Photo credits: Oystercatcher by Katie Nethercoat (rspb-images.com)

LOTE Logo credits: Saskia Wischnewski |