|

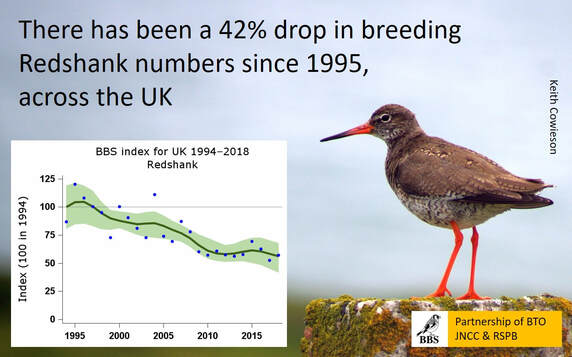

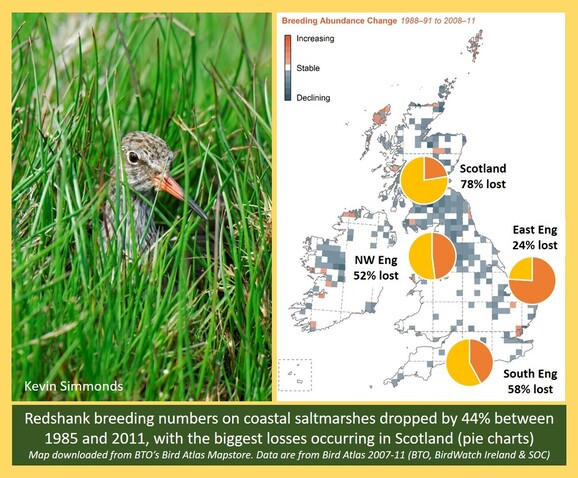

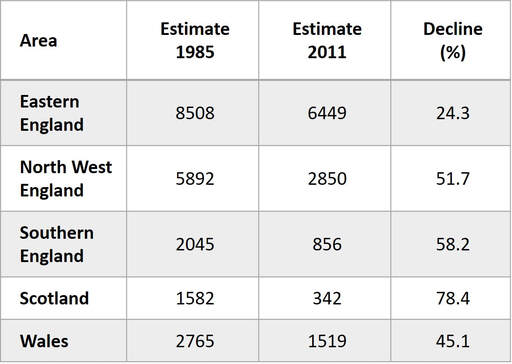

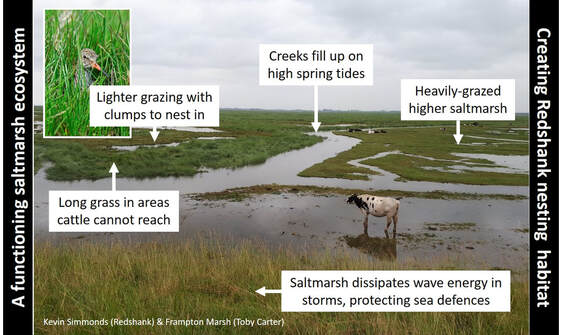

Guest blog by Graham Appleton, author of WaderTales. He has studied waders for over 40 years and is currently involved in wader research in the UK and in Iceland. He was Director of Communications at The British Trust for Ornithology until 2013 and is now a freelance writer and broadcaster. The noisy calls of Redshank, as they warn others of the approach of predators, proclaim ownership of territories or defend their chicks, is one of the most distinctive sounds of the coast during the summer. The RSPB and National Trust’s Life on the Edge aims to increase numbers of breeding Redshank by protecting and improving the saltmarsh habitat in which they breed. Redshank is an amber-listed species of conservation concern in the United Kingdom, with the most recent estimates of breeding population changes showing a drop of 42% between 1995 and 2018 (Breeding Bird Survey) and a larger decline over the period since 1975. About 25,000 pairs of Redshank breed in the UK (link to APEP4), with half of these nesting in coastal saltmarshes. Redshanks hide their nests in tussocks of vegetation but the chicks feed in more open environments, particularly around the edges of muddy pools. Nesting on saltmarshes Saltmarshes are intricate, dynamic habitats, where land meets sea. They are highly productive ecosystems, rich in plants, birds and insects. Traditionally, they would have been grazed by herbivorous mammals and waterfowl but, in the absence of free-roaming animals, the only way to maintain the short but diverse swards that harbour specialist plants and animals is to employ the services of cattle and sheep. Although saltmarsh still covers large areas, it is estimated that over 50% has been lost or degraded globally, with further losses occurring as saltmarshes are being squeezed between rising sea levels and hard sea defences that protect coastal settlements and farmland.  Anyone who has been out on a saltmarsh will know that they are not easy places to navigate, as they often have complex systems of meandering creeks that vary from small ankle-breakers hidden in the vegetation to deep, fast-flowing channels with slippery, muddy sides. With some local knowledge, it is possible to make your way from the sea-wall to the edge of the saltmarsh along a route that lies between two creek systems. On the other hand, travelling along the muddy, salting edge, parallel to the sea-wall, is difficult as it involves crossing creeks. Grazing animals face the same navigation problems; it’s a lot easier to graze wide expanses of the upper marsh than the outer areas that are dissected by deep creeks. These upper areas, with a mixture of short grass and clumps of longer vegetation, in which to hide nests, are also the ones that are favoured by breeding Redshank. How many Redshank breed on saltmarshes? A 2013 paper by Lucy Malpas (now Lucy Mason) in Bird Study brought together evidence of declines in saltmarsh-breeding Redshank over a 26-year period. An estimated total of 21,431 pairs were found to be breeding on British saltmarsh in 1985 but this had dropped to 11,946 pairs in 2011, with the highest proportion of the remaining population found in East Anglia. The 2011 survey showed that there were regional variations (see table), with the biggest declines in Scotland but also losses of over 50% in south and Northwest England. Looking at the way that saltmarshes were managed, Lucy found that Redshank declines were less severe on conservation-managed sites in East Anglia and the South of England, where grazing pressures remained low, but more severe on conservation-managed sites in the Northwest, where heavy grazing persisted. At the end of this Bird Study paper, Lucy and her colleagues suggest that saltmarsh-breeding Redshank declines are likely to be influenced by a lack of suitable nesting habitat. Conservation management schemes and site protection, implemented since 1996, appeared not to be delivering the grazing regimes and associated habitat conditions required by this species, particularly in Northwest England. Although habitat changes may not be linked to unsuitable grazing management in all regions, they suggested the need for a better understanding of grazing practices and consideration of potential long-term management solutions. Grazing levels and Redshank numbers Intensive grazing leads to a very short uniform sward, lighter grazing produces a more uneven patchy sward with diverse heights, whilst no grazing can leave saltmarshes with dense communities of coarse grasses. For Redshank, that need clumps of tall vegetion in which to hide their nests and more open areas in which chicks can feed, light grazing is a key management tool. Elwyn Sharps and colleagues, working on the salt marshes of the Ribble Estuary in Northwest England, investigated how grazing regimes worked for the local Redshanks. Elwyn showed that the risk of Redshank nest predation increased from 28% with no breeding-season grazing to 95% with grazing of 0.5 cattle per hectare per year, which is still within the definition of light grazing. You can read more about this in the WaderTales blog Big Foot and the Redshank Nest. In follow-up work, Elwyn showed that livestock play an important role in creating the clumps of Festuca rubra nesting habitat preferred by Redshank nesting on the Ribble Estuary but that even low-intensity conservation grazing can create a shorter than ideal sward height, potentially leaving Redshank nests more vulnerable to predators. One of the missing elements from Elwyn’s first two papers about grazing levels was an understanding of the behaviour of cattle on saltmarsh. In the next piece of work, Elwyn and colleagues tracked the movements of individual cattle, using GPS collars, and assessed the vulnerability of nesting Redshank, using dummy nests. In a 2017 paper in Ecology & Evolution, they showed that cattle spend their time in the same areas of saltmarsh as the ones that the Redshanks like to nest. Their conclusion is that “grazing management should aim to keep livestock away from Redshank nesting habitat between mid-April and mid-July, when nests are active, through delaying the onset of grazing or introducing a rotational grazing system”. Do conservation payments deliver? In recognition of the importance of saltmarsh habitat, agricultural grants have been available to support the management of saltmarshes, with a focus on providing an appropriate level of grazing for a range of plants, birds and insects. In their 2019 paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology, Lucy Mason and her RSPB colleagues asked some whether these agricultural subsidies are being well spent. This work is described in the WaderTales blog Redshank - the warden of the marshes. They concluded that, although there is sound scientific evidence as to how saltmarshes should be managed, it is difficult to encourage land managers to implement recommendations when these go against traditional farming practices and economic gain. Raising cattle on saltmarsh is hard work, in terms of stock control, but requires no fertiliser inputs. These ‘mobile mowing units’ stop saltings from becoming long and rank, thereby creating spaces in which a rich plant and grass community can flourish, where geese and waterfowl can graze during the winter months, and potentially providing nesting spaces for breeding waders, such as Redshank. Lucy and her colleagues conclude that agri-environment schemes are the only mechanisms through which saltmarsh conservation grazing can be implemented on a national scale, so it’s important to make sure that they are as effective as possible. By working together, it is hoped that policymakers, researchers and managers can refine conservation guidelines which are used to create management schemes that attract subsidies. Although half of the UK’s Redshank nest on tidal saltmarshes, significant numbers also nest in lowland wet grassland, on nature reserves and on low-lying pastoral farmland. These freshwater systems can be managed for breeding waders such as Lapwing, Redshank and Snipe. You can learn more about the tools available in the WaderTales blog Tool-kit for wader conservation, which summarises work led by Jen Smart (RSPB) and Jennifer Gill (University of East Anglia). One more problem!

As coastal communities are aware, sea-levels are rising and so is the incidence of summer storms. This is not good news for species that nest on saltmarsh, such as Redshank. In a naturally functioning ecosystem, the coastline would be receding, and Redshank would be moving inland. With hard sea walls protecting towns and farmland, it is hoped that new saltmarshes can be created in a few low-lying areas and that conservation management can be focused upon these wader hotspots. These new saltmarshes will not only provide space in which to develop biodiverse habitats that are great for waders, they can also capture carbon and reduce damage to coastal defences.

1 Comment

Guest Blog by Chris Goding, Hodbarrow Field Officer Following Dave Blackledge’s introduction to the recent LOTE funded habitat works at RSPB Hodbarrow, life at the reserve continues apace. I am one of two Field Officers here over the breeding season, with shared responsibility for surveying adult numbers and productivity of our key species (notably Sandwich, common, and little terns). We also monitor predation events and engage with members of the public about the RSPB’s work at the reserve, its history, and the wildlife found here. Work was finished on the new island in January this year, complemented by an extension to the eastern side of the main island. The new island has seen modest but encouraging interest from breeding birds, and is currently home to a ringed plover pair (with two chicks) and a single oystercatcher nest as well as 2 common tern nests. We are hopeful of increased use of the island in future years once the substrate matures. At the time of writing this blog, there are at least 20 common tern pairs on the new extension to the main island, making use of the increased space provided where a small island has been joined to the ‘mainland’, forming a miniature peninsula. Current trends point to a successful season all round!

The peak count of little tern adults so far this season is 87, with at least 40 pairs, more than triple the number of pairs last year! Twenty six little tern chicks were spotted during a ringing session on the 11th June, the highest count since at least 2017, so we are hopeful of an excellent year for the species here. They appear to be responding particularly well to the application of slag to the concrete surface at their favoured spot, which helps to prevent the accumulation of rainwater around the nests. Fifty common tern pairs (with a minimum of 40 chicks so far) points to a good year for this species too. Alongside this, at least 300 black headed gull chicks and 200 Sandwich tern chicks means the colony is a busy place. With time yet for these numbers to increase we are expecting a productive season at Hodbarrow this year. Guest Blog by Sarah Dalrymple South Walney Manager & Reserves Officer, Cumbria Wildlife Trust The gull colony at South Walney is an incredible one, and its fortunes over the years mirror strongly that experienced by the UK’s two commonest gulls, the herring and lesser black-backed gulls. Although a few gulls nested in the early 1900s, the numbers were steadily increasing. With the South end of Walney Island established as a Nature Reserve in 1963, regular and reliable counts were undertaken, and by 1974 an incredible 41,366 pairs of gulls – 22,751 herring and 18,615 lesser black-backed – were counted, making this largest colony in Europe at this time. Speaking to older birders who remember the height of the colony, a daily job at this time was to walk the tide line at low tide and collect the corpses of hundreds of gulls that had died from botulism over the previous day. The main food source for the colony was presumed to be a landfill 2.5km up the road from the colony; as this reduced in scale over the years until complete closure in the 1980s, the colony size declined accordingly. Remaining stable at about 10,000 pairs for a few years, the colony then started to suffer from mammalian ground predators. Remarkably, as Walney is only separated from the mainland by a narrow channel, foxes were not present on the south end of the island until the 1990s, and badgers not established until the late 2000’s. In 2011 Cumbria Wildlife Trust trialled temporary electric fencing of a part of the colony, which saw a notable success in fledging compared to the rest of the colony. Two large areas of the remaining colony were fenced – The Spit, a shingle area at the very southern edge of the reserve, and Gull Meadow, an area of semi-fixed dune on the western shoreline of the reserve. Although initially successful, a new problem arose in the mid 2010s. Year on year, several thousand pairs were fledging zero chicks. The most harrowing was in 2017, as we found a busy colony full of gulls and their young was carpeted with dead chicks only a week and a half later. This scene was repeated the following year. Necropsies were carried out by the Animal & Plant Health Agency, and it was identified that most chicks had been killed not by predators, but with “peck” marks. It was highly likely that the gulls were, in fact, killing their own young, or the young of their neighbours, and then not eaten – just left where they were. This is not an unknown phenomenon, as we’d seen this at Rockcliffe Marsh gullery, another site managed by Cumbria Wildlife Trust, and it has been seen at Gulleries in Texel, the Netherlands – although not to the same extent. We think that this intra-species predation is caused by the gulls experiencing extreme stress, loss of a food source plus predation pressure plus disturbance all adding up to cause the gulls to kill either their own or their neighbour’s young. By removing predation and disturbance from the Rockcliffe Colony, we managed to stabilise it after several years of zero productivity, and it is now a recovering colony successfully fledging young each year. At South Walney, a landfill just over the bay had closed in 2016, GPS tracking from a BTO project suggested our gulls had been feeding there; this closure led to a huge food source loss. And our electric fence was only mostly keeping the predators out; badgers and foxes were still sometimes getting through, but in 2020 badgers not only happily pushed through the fence, they dug a temporary sett right in the middle of the colony! By this point South Walney had dropped to under 1,000 pairs. Clearly something drastic was required to save it, and at least by removing any risk of predation we’d give the gulls the best chance we could. So thanks to our funders, this winter we erected a permanent fence, nearly 2m high, topped with electric, and with a horizontal “skirt” extending out underground 50cm to prevent any digging underneath. We enclosed almost the entirety of the Spit with this fence, double the area of the original electric fence. The eggs have started to hatch, and our counts reveal a new record low of just under 500 pairs. Will the new fence be enough to save the gull colony? |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

Photo credits: Oystercatcher by Katie Nethercoat (rspb-images.com)

LOTE Logo credits: Saskia Wischnewski |