|

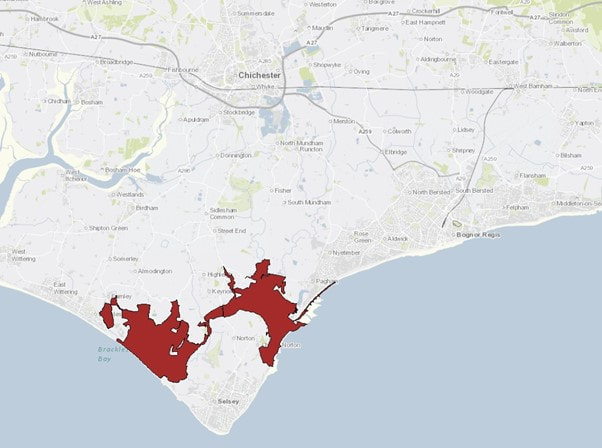

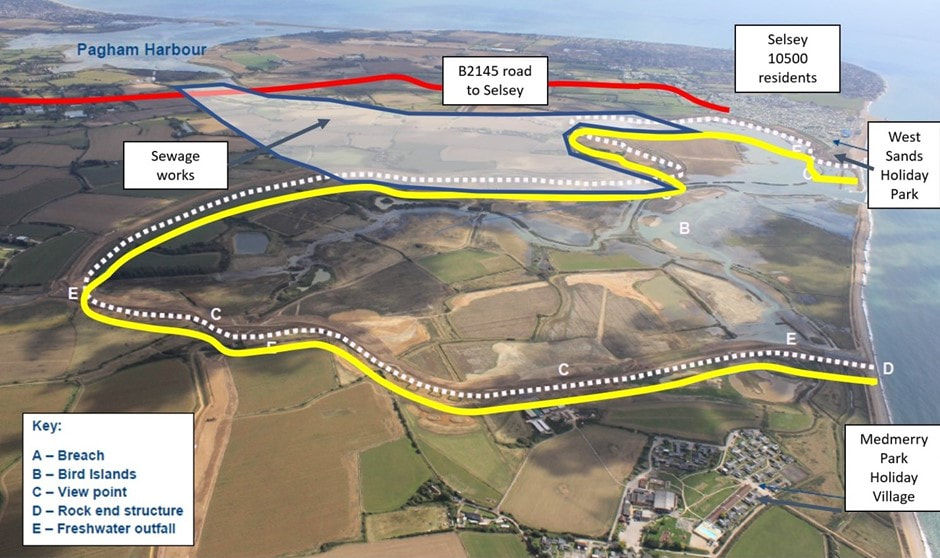

Guest blog by Mark Appleton, RSPB Bird Conservation and Visitor Engagement Officer On 31st October marked the start of the COP26 climate conference! For nearly three decades the United Nations have been bringing together almost every country on earth for global climate summits – called COPS – which stands for ‘Conference of the parties’. This year will be the 26th annual summit – giving it the name COP26 and will bring together world leaders and delegations to discuss all the gnawing issues holding countries back from curbing emissions and meeting the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. Delegations from most of the 195 nations that signed on to the Paris Agreement in 2015 will negotiate rules for a global carbon market, look to raise funds for climate action, and announce new emission targets. RSPB's very own Medmerry Nature Reserve is to be featured in a COP26 film. This particular event in COP26 will be hosted by the RSPB and Environment agency. Adam Taylor, a warden at Pagham harbour and Medmerry Reserves, said “Medmerry is being showcased during the COP26 conference in its event ‘Coast:Nature-based solutions for climate biodiversity and people – lessons learned and stories from the ground too’ along side examples from the Central Mangrove Wetland in Cayman Islands, Shanghai Chongming Dongtan National Nature Reserve and Jiangsu Yancheng Yellow Sea World Heritage site in China and the South Korean Yellow Sea Getbol World Heritage Site, as successful examples of habitat restoration in coastal wetlands” So why do we think Medmerry is so important? Medmerry Nature Reserve is a flood protection scheme as well as a home for wildlife. After severe flooding on the Manhood Peninsula, the Environment Agency started construction on Medmerry in 2010. At the time of construction, it was the largest coastal realignment scheme in Europe. It was completed in 2013, it protects at least 348 properties, a sewage works and roads serving 5000 residents. The earth embankment originally built in the 1960’s to prevent the sea flooding the land was intentionally breached so that natural mudflats and salt marsh are slowly being created by the advancing tide. Saltmarsh has great ecological value for the ecosystem, namely in nutrient regeneration, primary production, habitat for wildlife species, and as shoreline stabilizers with the bonus of it being a great carbon sink. This amazing scheme has been recognized by COP26 and are featuring the great habitat of Medmerry. 183 hectares of intertidal habitat were created, and many species have made use of it. Bird populations are generally decreasing across the UK, but there is some good news at Medmerry where they are increasing – especially for farmland birds and waders! We now have at least 32 species of fish present and the reserve is an important nursery for their young.13 species of mollusc have colonised and 11 more are expected to in the coming years. Medmerry is home to 4 of Britain’s reptile species, mammals like water vole and roe deer and a multitude of insects like butterflies, dragonflies and crickets. BUFFER ZONE As well as being a vital habitat for thousands of waders and waterfowl, the role that saltmarsh plays in defending our coasts from erosion by waves is increasingly recognised, and efforts are being made to protect and restore them. Although saltmarsh tends to need little conservation management, many have a long tradition of low-intensity grazing, which is important in maintaining their diversity. Re-alignment of sea-defences can allow for expansion of this habitat. Images of storm surges, rising sea levels and flash floods and the devastation they wreak on people and their homes are becoming all too common. Due to the melting of artic sea ice and thermal expansion of the oceans as a result of global warming, sea levels have begun to rise. As with all coastlines, this rise in water levels is predicted to negatively affect salt marshes, by flooding and eroding them. This has a knock-on effect to our nesting and roosting sea birds with their habitats disappearing. Saltmarsh act as a buffer zone, stabilizing shorelines and protecting coastal areas, inland habitats and human communities from floods and storm surges. The salt marsh also breaks up the wave action acting as a barrier. When flooding does occur, our salt marsh acts like a huge sponge, soaking up the excess water. Worldwide, these ecosystems are in danger of disappearing if they cannot increase elevation at rates that match sea-level rise. CARBON SINK Saltmarshes can be very efficient at locking away carbon. When saltmarsh plants die, rather than decomposing and releasing their carbon into the atmosphere, they become buried in the mud. As sea levels rise more sediment layers get buried and more carbon gets locked beneath the mud. The rate of carbon sequestration on coastal wetlands is greater than in all forests combined, despite forests covering much larger areas. As trees grow, they absorb carbon from the atmosphere and this carbon remains in the tree if it lives. When these trees die, they decompose and release the carbon back into the atmosphere. What happens in wetlands is different and means the carbon can be stored for hundreds of years. Wetlands are special because they bury the carbon from decomposing plants before it can be released back into the atmosphere. Saltmarsh has two main characteristics which allow them to act as efficient carbon sinks. They have a high vegetation growth rate with European saltmarsh soils sequestering an average of 2.1 t C/ha/yr. Secondly, they do not emit methane, an important greenhouse gas, since the sulphide present in the soil inhibits bacterial-driven methane production. The water levels and occurrence of anaerobic decomposers in tidal marsh ecosystems also acts to reduce organic matter decomposition and promote carbon storage. Salt marshes are very important in sequestering carbon and do so at a higher rate than land ecosystems. The saltmarshes at Medmerry is therefore very important in storing carbon. The science is clear. Wetlands are the most effective carbon sinks on the planet. CONSERVATION Saltmarsh is a scarce resource in Britain. They are threatened by human development expansion, invasive species, erosion, altered hydrology and connectivity, and climate change. It is estimated that over 50% has been lost or degraded globally thanks to reclamation and erosion. Further losses are occurring, as saltmarshes get squeezed between rising sea levels and the hard sea defences that protect coastal settlements and farmland. In the UK we are losing nearly 100 hectares of saltmarsh a year (that’s nearly 150 football pitches). Economic analysis has shown some of the economic benefits of saltmarsh. 2207 tonnes of net carbon can be sequestered per year in restored saltmarshes. 74 million pounds in benefit from restored salt marshes to flood defences over 40 years. Damaged wetlands can turn from a natural carbon sink into a source of CO2 emissions that adds to global warming. Many of the wetlands which remain are in a fragmented and degraded condition. But we mismanage our wetlands at our peril. The past two decades have seen a shift toward working with managers to restore tidal marshes to conserve existing patches or create new marshes. In recognition of the importance of saltmarshes, agricultural grants are available to support their management, with a focus on providing an appropriate level of grazing for a range of plants, birds, and insects.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

Photo credits: Oystercatcher by Katie Nethercoat (rspb-images.com)

LOTE Logo credits: Saskia Wischnewski |