|

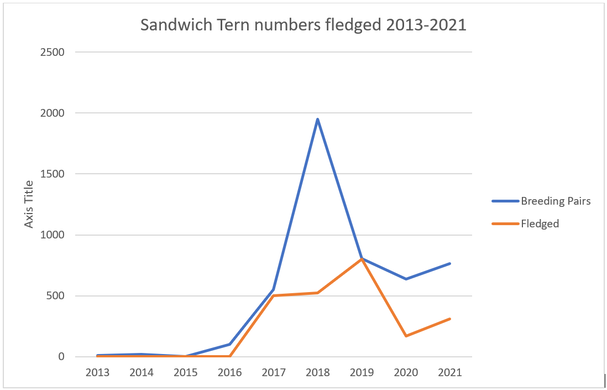

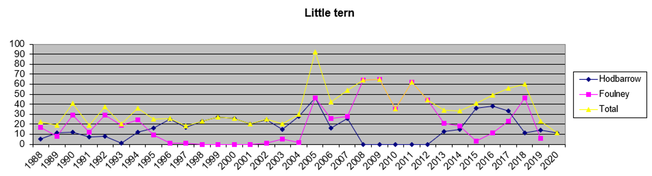

Blog by Mhairi Maclauchlan, RSPB Cumbria Coast Reserves Warden Hello, I’m the Warden for the Cumbria Coast Reserves and I’ve been asked to give a summary of our long term tern numbers at Hodbarrow. Hodbarrow is a large lagoon in the south of Cumbria formed from a former iron ore mine. It’s calm waters and iron ore slag islands provide ideal habitat for nesting birds in particular seabirds such as terns, ringed plover, oystercatcher amongst many more. Previously my colleagues have written about the work being carried out at Hodbarrow over the last year thanks to EU Life on The Edge funding. In addition to what is happening presently it’s very important for to look at historic trends in the data, examine the reasons for those trends and use these to help shape our management. Using historic data as well as data collected by the dedicated wardens we have had in place over the last 5 years, we can see how numbers have changed. When looking at data we tend to look at population size and productivity. Numbers of nests only give us a small glimpse into the breeding season it can also be useful to investigate the productivity of those nests. When we say productivity, we mean the success of each individual nest to raise young to fledging age and the numbers of fledglings coming from each nest. Fledging survival to breeding age isn’t guaranteed but we still think of that nest as productive. Numbers of nests, in simple terms, show us what birds arrived to breed on the habitat we have however productivity shows us how many chicks were produced from those nests that will now be part of the population. Focusing on Hodbarrow you can see from the graph below that Sandwich terns would arrive and not progress to nesting or fledging stage and have shocking productivity. After several years of this trend in the winter of 2015/16, we installed an in-water fence to stop predators such as fox accessing the island and decimating the nesting birds. This was also the start of our employment of summer wardens who were responsible for managing disturbance and large gull predation. As you can see after these measures were implemented birds were able to settle and breed as well as successfully get chicks fledged. South Cumbria Populations It can be very tempting to focus in on your site and what is happening locally, when in reality birds don’t see a boundary or a fence on the map. A few years ago, we came to the realisation that we had to look at Hodbarrow numbers (successes and failures as well) in terms of South Cumbria, national and even international populations rather than focus on purely Hodbarrow numbers. This gave us a wider and better understanding of what was driving our population changes. There are two main tern colonies in South Cumbria – Hodbarrow and Foulney. They are geographically very close to each other as the tern flies. We work closely with the Wildlife Trust who manage Foulney, sit on working groups with them and we have also worked together throughout Life on The Edge funding. We see the birds at Hodbarrow as very much part of the South Cumbria population. Often the overall number in the population of birds in South Cumbria stay the same however they utilise both sites. One year they can all be at Hodbarrow and another year the population can then move over to Foulney. The graph below shows the population changes for little terns over 30+ years. You can see from the graph that from 1996 – 2003 little tern numbers were concentrated at Hodbarrow and similarly from 2008-2012 Foulney held most of the birds, however overall, the population number stays roughly the same. The trends in the Cumbrian population shows that even though there are years where birds aren’t present on a specific site, we still have to make sure the habitat is great and that work carries on to provide tip top potential nest site which they may utilise during the season or in subsequent years.

Interestingly, we have even seen this trend with colonies further afield. In 2018, we had the best ever year for Sandwich terns at Hodbarrow / South Cumbria however this involved birds re-locating from Cemlyn, Wales. Within days of a mass desertion at Cemlyn due to increasing otter predation a large influx of birds arrived at Hodbarrow. We can only surmise that these birds may have made the journey up the coast and the dates certainly provided evidence in favour of this.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

Photo credits: Oystercatcher by Katie Nethercoat (rspb-images.com)

LOTE Logo credits: Saskia Wischnewski |