|

Blog by Kieren Alexander - RSPB Site Manager, Old Hall Marshes Reserve Last Summer and Autumn was a time of high activity at Old Hall, as the next round of LIFE on the Edge works was completed. Like in previous years, the focus of the work was on reprofiling footdrains to benefit breeding waders by improving edge and then using this claimed material to rebuild and repair some historical but damaged crossing points. The latter for the purposes of allowing us finer and greater water control and greater compartmentalisation of the marshes. However, this time we also completed the installation of a new tilting weir with eel pass, this is an important update to the site’s infrastructure. It replaces an old, leaky and somewhat difficult to use wooden dropboard sluice with a new purpose built easier to use at all water levels sluice. The important part of this is the ability to use the sluice at all water levels, in the event of a saline incursion our ability to remove water from the marshes will be critical. This weir with its safe access route will enable us to do this. The other improvement reducing the amount of freshwater that was being lost through the old dropboard, freshwater is critical to the health of the marshes and is one of the things we can’t control. Although it may sound odd to have an eel pass on this, the borrowdyke where the weir is placed is hardly a main river, as eel numbers have dwindled freshwater marshes near the sea have become increasingly important as refuges for this species and is now home to a good number of eels. This eel pass will allow the eels that call Old Hall home to complete their natural lifecycle. It will ease passage into the marshes and then when the time comes allow them to leave the Marshes and return to the Sargasso sea to spawn, it what must be one of the most incredible migrations of any animal. During the works we were reminded of some of the pressures that are increasingly prevalent to highly valuable and designed sites, this time in the case of a wildfire which ripped through around 10ha of scrub on the marshes. Incidents like this remind us of why we need to start the careful adaptation of our protected sites and change the way we work. Later this year, we will be concluding our LIFE on the Edge work at Old Hall, with the installation of some new solar pumps but before that we have the breeding season to navigate, although we may not have received the water we would have wished for this winter (we seem to have been stuck in a dry high pressure system for months), the key fields are more or less where they need to be and before long lapwing will laying eggs and raising young across the marshes.

0 Comments

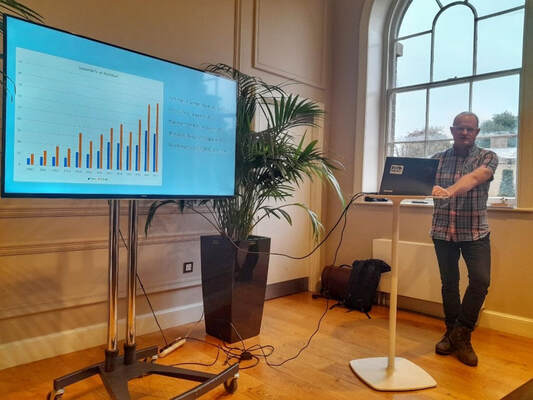

Blog by Lizzie Bruce, RSPB Senior Project Manager (seconded) Spoonbills were once a common site across England and Wales, so common that they would be served at banquets as a delicacy. However, the draining of the East Anglian Fens and continued hunting drove the species to extinction in the UK, with the last nesting attempt in 1668 at Trimely, Suffolk. Fast-forward three hundred years to 1997 Spoonbills attempted to nest once again in east England but it wasn’t until 2010 when a regular colony became established at Holkham National Nature reserve, in Norfolk. Breeding Spoonbills (credit Andy Bloomfield) Today, the UK population has increased to 69 pairs, with colonies found in Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk, Yorkshire, and Cumbria. The recolonisation is likely to be linked to the growing population in the Netherlands and the restoration of wetlands in the UK. But also, the dedication of reserve staff, in particular Andy Bloomfield, Senior Warden of Holkham National Nature reserve who has been instrumental in better understanding the ecology and behaviour of spoonbills in the UK, translating this into conservation action. At the end of 2022, 50 conservationists across England came together at Holkham to attend the first UK Spoonbill Workshop. Developed by Andy, hosted by Holkham Estate and with support of LIFE on the Edge, the workshop aimed to discuss the status of the Spoonbill and its future in the UK. Networking with colleagues (credit Steve Rowland) We began the day with Lord Leicester, providing an overview of his family estate at Holkham, sharing insights into how the land has been managed over time and the odd recipe from old game cooking books. Lord Leicester opening the Spoonbill workshop. (credit Steve Rowland) The first session focused on Norfolk Spoonbills with Andy providing an overview of Spoonbills at Holkham Estate and the wider Norfolk landscape. 2022 was a momentous year for Norfolk Spoonbills with two further sites successfully fledging young. One of which was in a woodland neighbouring Norfolk Wildlife Trust Cley Marshes Nature Reserve. George Baldock, NWT Warden, and Alice Littler, owner of the woodland, shared with us their joy and excitement in discovering breeding Spoonbills within the heronry. Andy Bloomfield (credit Steve Rowland) Moving out of Norfolk for the second session, we hopped across the border to Suffolk which is home to the UKs only ground nesting colony of Spoonbills. With good numbers of summering Spoonbills various methods were trialled to encourage them to breed, including the use of decoy birds and artificial tree platforms. In 2019 Spoonbills opted to nest underneath the platforms! However, ground predation has been a problem, so an in-ditch predator exclusion fence was installed increasing the success of the Spoonbills and the Herring Gull colony they nest within. We moved north to RSPB Fairburn; a site where spoonbills first bred in 2017. So far, this is the UK’s most inland colony, commuting along the M62 to feed on The Humber Estuary. With an established Spoonbill colony, plans are in place to create further safe areas at Fairburn and neighbouring wetland sites. Finally, we moved northwards once more, with an overview of Spoonbills in the north of England & southern Scotland. Here there have been several nesting attempts within mature unmanaged wetland sites close to the estuaries. Success has so far been limited. We finished the morning with an overview of the wintering population of Spoonbills at Poole Harbour, which currently peaks at around 80 birds. In Poole Harbour, the Spoonbills favour the less disturbed areas, so with high levels of disturbance, especially during the warmer spring & summer months this maybe part of the reason as to why they have yet to stay and breed in recent years. After lunch we enjoyed a pre-recorded talk from Petra de Goeij, who provided an in-depth overview of Spoonbills in western Europe. The population has grown from 500 pairs in the mid 1980’s to approximately 9500 pairs today. On the mainland in Netherland’s Spoonbills were experiencing high levels of predation, however they have since discovered the predator free islands within the Wadden Sea, resulting in the population going from strength to strength. In the Wadden sea the Spoonbill population is primarily ground nesting within saltmarshes and Herring Gull colonies. Spoonbills nesting within Herring Gull colony, Wadden Sea (credit Jan Skriver) Traditionally Spoonbills have migrated south through France, Spain, Morocco to Mauritania. However, through colour-ringing studies it has been shown that there is higher survival when birds winter in Europe, compared to migrating south to Mauritania & Senegal. Over time more Spoonbills are now wintering in the Netherlands, rather than migrating south. We finished the day with an overview of Spoonbill Ecology from Graham White, which neatly summarised the day’s talks. Key take home messages

Typical nesting habitat of Spoonbills Image credit: Andy Bloomfield The future

For managers with breeding Spoonbills Protect and manage your existing nesting areas ensuring:

For managers of potential Spoonbill breeding sites

In conclusion it was an inspiring day, bringing together conservationists across England who are working on the ground to protect and restore species such as the spoonbill for years to come. Blog by David Mason, National Trust Ranger After a busy summer and autumn, much of our coastal adaptation work on the island has paused for the winter and the site is closed to visitors. Brent geese and other waterfowl and waders now have the place largely to themselves. WeBS counts have recorded a wide range of birds on and around the island with avocet, curlew, golden and grey plover, redshank, dunlin, lapwing, black-tailed godwit, wigeon, teal and Brent geese being most numerous. Other species, mainly clustered around the new freshwater pond, have included yellow wagtail, linnet, whinchat and kingfisher. This has been a very useful source of freshwater for birds during the extended dry and hot weather this year, although levels dropped severely towards the end of the summer. This also led to new hedge plants suffering, which had to be watered several times to keep them alive. Blanket weed smothered newly planted marginal plants as the water levels dropped as well. Volunteers helped with the watering and clearing blanket weed. The abundant autumn rain has provided a welcome top up for the water features on site, however. Water vole translocation As I mentioned in my last blog the road to establishing new saltmarsh is a long and complicated one, and involves a number of stages and licenses which need to be complied with and completed before the next one can be implemented. One of these has now been completed. Following a successful process of habitat creation, trapping and translocation, 16 water voles have now been relocated to their new home out of the reach of the sea on Northey Island. As part of a Natural England licensed translocation of a protected species a new freshwater pond was created in 2021 and vegetation has since established to provide a new home for water voles (as well as being popular with local birds, as mentioned above). The vole’s less-than-optimal, existing habitat is threatened by inundation by the sea and is to be realigned as part of the LIFE saltmarsh creation project. The voles were trapped and translocated over several weeks by licensed professionals. The voles are carefully removed from the traps in cages, with tubes from a well known brand of crisp, their ideal hidey hole in transit. These are then used to place them into bottomless release boxes dug into the bank of the receptor pond. The voles can feed on provided carrots and apples and then burrow out when they are ready. The fence around the pond will keep them contained until they are fully established and the managed realignment works are completed. When removed, the voles will have access to a wider network of ponds and ditches around the island. Monitoring of the voles will continue to check on their progress over the coming years. The way is now clear to remove part of the embankment next year to allow the tide in and begin the next phase in process of establishing new saltmarsh. Visitor facilities A new path has been installed to the hide, which overlooks the new vole pond and what will be the new intertidal area following the embankment realignment. If they are lucky visitors may see a vole or hear a plop as they enter the water. Along the track we have also installed a viewing platform and bench overlooking the river and mudflats towards Maldon. I led a guided walk for visitors in September to talk about the threats to saltmarsh from climate change and sea level rise and the importance of the managed realignment and habitat creation project in contributing to saving this habitat. Attendees were able to use the new facilities for the first time. Remembering the history of Northey As well as providing important habitats for local wildlife, the island was also the site of Battle of Maldon between Anglo Saxon and Viking armies, which took place here in 991AD. This is commemorated in an epic Anglo Saxon poem and an exciting Lego renactment on YouTube. The latter captivated year 5 pupils at a local school to whom I recently gave a talk about the island as part of their studies of the Vikings. Nobel Peace Prize winner Sir Norman Angell also lived here in the 20th C. Links to previous blogs about Northey Island Part 1: www.projectlote.life/news/northey-island Part 2: www.projectlote.life/news/ntconservationadaption Blog by Kieren Alexander, Site Manager for RSPB Old Hall Marshes After the successful recharge operation of Autumn/Winter 2021, attention has now turned to monitoring both the breeding colony present on the island and of course how the sand and shingle is moving and responding to the water. Thankfully its good news on both fronts! Starting with the little tern colony and other beach nesting bird that nest at Horsey. Little terns had a great year, with 22 nests fledging 19 young. There were 14 AON’s on the new recharge and a further 8 on the old recharge, this is an increase of 5 nests and 11 fledged juveniles from 2021 and a welcome return to form for this colony that decreased during 2020 and the impact of recreational disturbance. Ringed plovers did well, with all four pairs of young fledging at least one chick each. Oystercatchers stayed stable at 10 pairs and there were the normal low levels of black headed gulls. We are thankful to the environmental team at Tendring District council, in particularly Leon Woodrow for erecting signage and closely monitoring the species and any potential disturbance over the summer months. What has been impressive is the way the little terns immediately colonised the new area of beach, with many nests found on this new area, this shows the importance not just of safeguarding existing colonies from the impacts of climate change (which was one of the aims of the project) but also the vital need to create new habitats for our species. As well as the beach nesting colony we have also been monitoring the sand and shingle and how it is moving in response to tide and wind after being recharged. We are lucky at Horsey in that we have real life model that was created in the 1990’s in the form of the existing beach (to the west in the photo). So, we have a strong idea of how the material will respond. However, it is always nice to see the theory become reality. The GIF below shows the results of our monitoring since the material was deposited, so far, we have undertaken three monitoring flights and it shows the material initially being smoothed out and then gradually being pushed landwards towards the existing beach and then following a classic longshore drift movement to the west, making it a near mirror image of the existing beach.

Movement has been slow so far, but it is assumed that the material does a lot of its moving in the winter season, so the next results of the next two flights will be interesting to see and how it continues to respond. In case you missed it, here is the link to first part of Horsey Island Recharge Project blog, the second part and the third part. By Audrey Jost - Assistant Warden at RSPB Seasalter Levels and Blean Woods May 2022 saw the completion of the habitat restoration works at Seasalter Levels. This massive project enabled the creation of 40 crossings/dams, 50 bunds/plugs, 20 islands and nearly 120,000 m2 of rills and scrapes, connected to waterways via culverts and elbow pipes. Over 2,000 m of ditches were restored and 3 trailer mounted water pumps were purchased to replace defective trash pumps, with solar pumps planned to be installed in 2023. 4,000 m of stock fencing and 3 new livestock corrals also were installed, allowing us to introduce large-scale grazing across the reserve. The addition of a bridge linking Alberta and Whitstable Bay Estate, in the north of the reserve further increased connectivity across the site. Spring brought colourful changes to the site as bunds and islands transformed from dark brown to bright yellow with the apparition of bulbous buttercups. This attracted lots of pollinators, with 365 bumblebees recorded by our volunteer surveyor in Alberta, our highest number since starting in 2018! The highlight of this survey was the record of 5 shrill carder bees, one of the UK’s rarest bumblebees. Several shrill carder bees were also spotted on the other side of the bridge in Whitstable Bay Estate, indicating that the species is slowly colonising the site. Unfortunately, we were unable to efficiently control water levels and flood fields this year due to the inability to obtain an abstraction licence. The licence acquisition is however planned for 2023, with a year’s worth of water levels, salinity and flow rates monitoring required by the Environment Agency. Despite all this, the breeding season at Seasalter Levels showed encouraging results, as a small part of the site retained rainwater naturally. Species that successfully bred on the reserve included lapwings, little grebes, pochards, shovelers and gadwalls! After breeding season was over, we carried out habitat management tasks, putting our new tractor into good use as we undertook topping across the site. Despite the site quickly drying out due to the drought and the impossibility of pumping, many different species visited the Levels throughout summer. They ranged from waders such as greenshank, redshank, green and common sandpipers to raptors such as hen harrier and hobby. Rarer birds such as purple heron and glossy ibis were also amongst the reserve’s visitors. We even had a surprise bittern in the reedbed! The remaining water pockets of the site are not to be outdone. The newly created shelf in the main ditch between Alberta and Whitstable Bay Estate is a good example where up to 30 little egrets are seen on a regular basis! If you’re lucky, you may even spot cattle egrets amongst them! 5 months after the official end of the habitat works, the restoration of Seasalter Levels is still a work in progress. Changes are definitely happening but it will take time for the reserve to become a fully functional wetland. Stay tuned for future updates!

Links to the previous blogs on the restoration of Seasalter Levels: Part One and Part Two |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

Photo credits: Oystercatcher by Katie Nethercoat (rspb-images.com)

LOTE Logo credits: Saskia Wischnewski |